By Tess Shingles, Assistant Curator, Queensland Stories

Do you believe in fate? A preordained destiny?

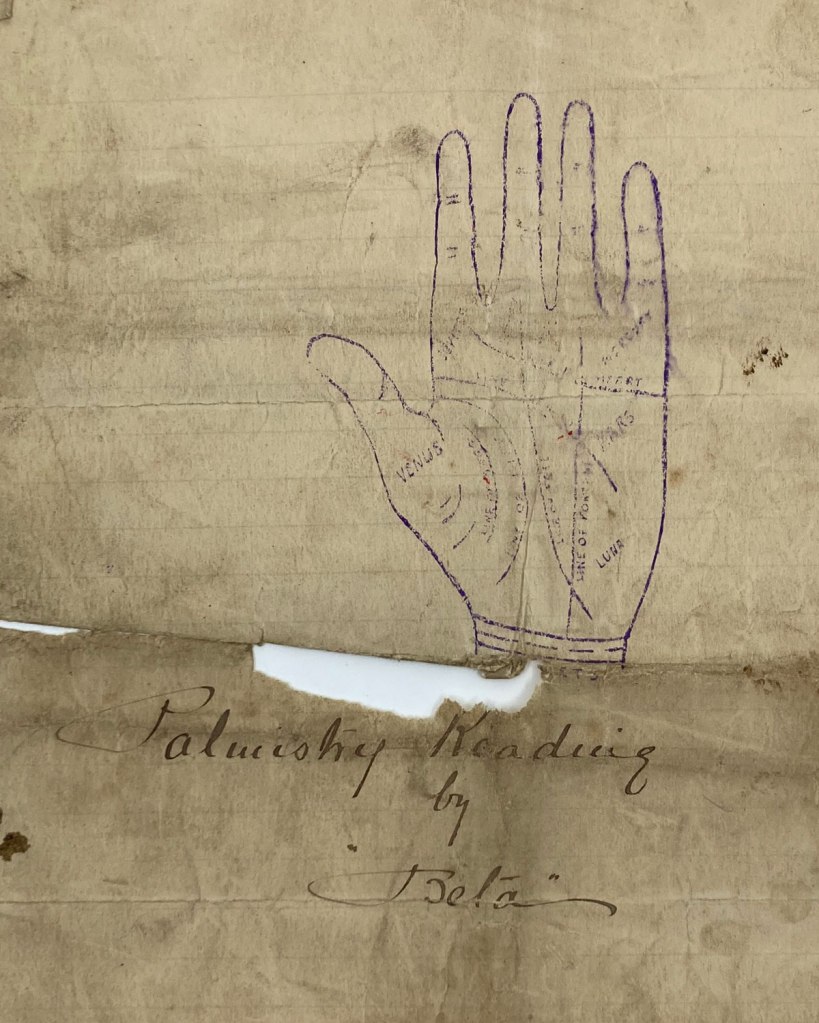

A woman living in Mt Morgan in November 1900 believed enough to pay for a palm reading. The well-worn but carefully kept document hints at how its owner valued these six pieces of paper.

While her name has been lost to time, her handwritten fortune is held in the Queensland Museum’s collection and from it we can learn a lot about fears and desires at the start of the 20th century.

Many of the themes would not be unusual in a palm reading today; family, wealth, travel, sickness, and mortality but looking more closely we start to see contextual differences emerge.

Marriage

Due to contemporary laws and marriage conventions, it is likely that the fortune pertained to a young woman as it refers to her future “husband”.

Beta, the fortune teller, outlined a “happy married life” but interestingly didn’t mention love, perhaps hinting at the more transactional role that marriage played at the time. He expected her to marry between 23 and 28 but most likely around age 26. It should be a happy marriage if she chooses a husband wisely. Beta advised,

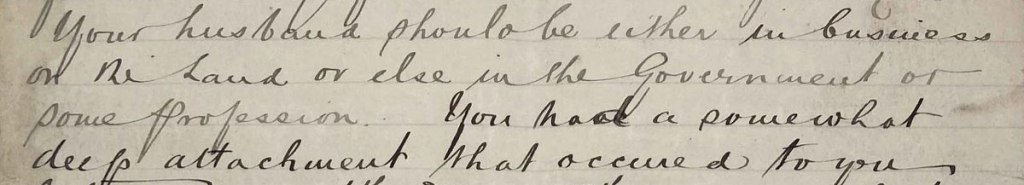

Your husband should be either in business on the land or else in the Government or some profession.

It is interesting that Beta here seems to provide advice rather than prophecy, counselling on what the women ‘should’ look for rather than what ‘will’ occur. Perhaps he was accounting for his patron’s location in Mt Morgan, a gold mining town in Queensland, and warning against a husband who has a fluctuating or sporadic income, like gold mining.

The fortune illustrates the expectations of many married woman at this time. While many did (or had to) work, there was heated debate and social pressure around whether a woman should work.

At this time, work – in particular women’s work – was an indication of the economic status of the family. While wealthy women had the freedom to focus on social rituals, home decorating and their reproductive roles, women in poorer circumstances generally had to work (as well as rear children), often in domestic service or factory work roles.

Middle class women, however, had the pressure of ‘marrying well’: choose wisely and they would not need to work. Choose unwisely and they would not only have to work, but also become associated with the lack of respectability this implied (The Sunday Sun, 1909 and The Armidale Express, 1926).

It is important to note that married women were banned from working in the public service until 1969 so the supposedly ‘respectable’ professions of teaching and nursing were not possible once wed. It was most likely the geographical location and these contemporaneous social considerations that underlie Beta’s advice to seek a husband with a stable income.

Wealth

According to our fortune teller, the woman was “not likely to be poorer at any time than the present”, again perhaps hinting at a judicious choice of husband (or an inheritance).

It would not have been possible for the woman to have or continue her own source of income as married women were not allowed to work. The woman is warned she “should not speculate as you have not the power to win Neither Mining nor Racing”. This is not as odd as it seems. Women were involved in horse racing in Queensland during the second half of the nineteenth century attending as spectators, placing bets and in some cases calling odds.

Such measured, risk-adverse guidance is contrary to the contemporaneous fear mongering around fortune telling, which suggested that practitioners looked to manipulate the weak minded into risky or misguided decisions. Such manipulation appears to be absent from Beta’s reading and he offers sensible, generalised advice around money. Although some of his other predictions do become more specific.

Travel

Beta confidently claimed the woman would travel twice in the next six months – once by land and once by sea – with one trip bringing “some element of disappointment”. But it could’ve be worse, and thankfully Beta described the voyages as “free from danger”.

You can travel on the sea in safety no fear of shipwreck or of drowning Water and liquids are friendly for you and will not hurt or harm you.

This prediction of course reflects one of the main modes of transport in Queensland in 1900, when coastal shipping was often the only way to travel between major ports and centres. At this time, traveling for leisure was generally for the wealthy and elite but young, unmarried women might travel for work (teaching or nursing) or for marriage.

In this instance, the travel promised to our fortune seeker came with a safety assurance, one that, thanks to technological advances, wouldn’t be an immediate concern when starting out on a sea voyage today.

Sickness and mortality

Concern with mortality featured prominently in this reading. Beta promised the lady she would live to the “age of 65 to 70”, and would outlive her husband, both of which were general expectations for Australian women in 1900.

The woman was warned that she would be seriously ill in her 35th year and that her middle child (of three children) would be more susceptible to illness although all of her children would live into adulthood. There were also predictions like tripping and falling which may occur under very specific circumstances.

Be careful during the next four to eight weeks in mounting up anywhere into conveyances, stairs, steps &c. as you may fall and shake yourself so as to invalid you for a day or so. This will come to you only if you are careless and seems to be caused through an animal.

The fortune’s obsession with mortality and illness reflects the context of a woman living in rural Queensland in 1900.

Infant mortality was 34 times higher than today and meant that many children wouldn’t live to adulthood (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002). People would often have to travel for healthcare that might not have advanced enough to cure their condition.

Death was far more present in the lives of Queenslanders in 1900 than it is today, and mortality is one of the motifs recurring in this fortune.

What makes for a fortunate life?

Today, there are elements of this palm reading that strike the reader as old-fashioned, such as the lack of female agency or 65 years being considered a long life. Yet many themes of human concern in this fortune remain the same today: family, wealth, travel, illness, and mortality.

One wonders if this predicted life came true for her.

Of all the possible outcomes, we doubt she would have foreseen that these predictions about her life received by post were fated to be a part of Queensland Museum’s collection over 120 years later.

Want to find out more about the fortune-teller Beta? Read my other blog here or see the full transcription of the fortune in our online collection.

Sources ↴

“Coastal shipping in 19th and 20th Century Australia“, State Library of Queensland, updated October 2019, accessed 5 June 2023.

“Day at the races: the horse in Australia“, State Library of New South Wales, updated 2016, viewed 5 June 2023.

“Mortality and Morbidity: Infant mortality.” Australian Bureau of Statistics, 9 May 2002, Date of Publication or Update Date.

“WHY WOMEN HAVE TO WORK.” The Sunday Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1903 – 1910) 2 May 1909: 10. Web. 15 Jan 2024.

“Women Who Work” The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW : 1856 – 1861; 1863 – 1889; 1891 – 1954) 6 August 1926: 11. Web. 15 Jan 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.