By Tess Shingles, Assistant Curator, Queensland Stories

Did you know that in 1900 you could pay to have your palm read by post?

Did you know that to do so was illegal?

The Queensland Museum collection holds one such illicit fortune from 1901. While the recipient remains a mystery, the writer, a palm reader named Beta, gives us a glimpse into the world of fortune telling in Queensland at the start of a new century.

The Palm Reader

Classified advertising from 1900 reveals the popularity of fortune telling at the time with many advertising in the “Personals” including our fortune teller, Beta. He advertised as an “Englishman” who was schooled in the Indian palm reading tradition.

As a male, Beta was in the minority within his profession as the role of fortune teller was often assumed by women who were able to add to the income of their household through this practice (Piper, 2015). Historically, fortune telling gave women power and agency but it was also sometimes seen as akin to witchcraft and heresy. This negative perception, albeit with a modern twist, was held by many of Beta’s contemporaries.

The Crime

Fortune telling was illegal in the colonies in 1900 with many believing practitioners were charlatans out for money at best, and a serious threat to a moral and rational society at worst (Queensland Criminal Code, 1899). This fear was based in the control it was perceived that these seers had over their clientele, the opposition it posed to rationalism, and barely veiled racism.

There existed a generalised fear that fortune tellers could influence their clients into immorality and that it went hand in hand with other crimes like theft and prostitution (Piper 2015). Even casual social participation was discouraged as “these fortune-telling people were generally foreigners, whom it was not desirable to encourage- idle persons who were really vagrants” (Queensland Legislative Assembly, 1899).

Fortune telling was often associated with the Romani, so it is interesting to see Beta advertise as an “Englishman” perhaps to distance himself from this foreign and often impoverished archetype of the fortune teller. It was argued that the practice was an example of lower-class pursuits corrupting the respectable middle classes.

Outlawing fortune telling in theory would eradicate this moral scourge but catching the criminals proved more difficult. To prosecute, police would have to witness money changing hands. Many classifieds at the time advertised fortune telling, often multiple times per paper, but are careful to leave out the concept of payment, as we see with Beta’s advertisements.

The Advertisements

Advertising was a great way to legitimise your practice. Dr Alana Piper, researcher at the University of Technology, Sydney, highlights how fortune tellers would employ different tactics to do this depending on their gender (Pietsch, 2020). Men, in particular, would try to align their practice with pseudo sciences of the age also demonstrating phrenology, character reading, and psychology.

It appears that Beta tried this marketing tactic, claiming he studied with “Hindoo Adepts” of the “Indian system” which he claims is the “oldest, most scientific” method (The Brisbane Courier, 1900). Advertising not only served to tout the legitimacy of the fortune tellers’ trade, but it would also let you know where to expect them next.

Beta advertises a Brisbane premises in early 1900 in Queen Street but was also known to travel with his services, which no doubt maximised his clientele and exposure.

He travelled to Toowoomba in July 1900 (Darling Downs Gazette, 1900), and in late August 1900 he is advertised in the Gympie Times as “coming soon” (Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, 1900). It appears he returned to Brisbane in early February 1901.

The Fortune

The fortune from the Queensland Museum collection has the stamp of his Brisbane offices but “Mt Morgan Nov 3rd 1900” as the recipient’s location. This was at a time when he was not actively advertising in Brisbane and his last classified advertising mentioned he was travelling north. This suggests that the fortune may have been commissioned by post while Beta was travelling north – a service that Beta offered according to his advertising.

How did this consultation occur? As half of the correspondence is missing, we can only guess. Other contemporary examples suggest she may have sent an ink transfer of her handprint, a trace and drawing of her most significant palm lines, or even a photograph of her hands (Hill, 1893, Meier, 1933).

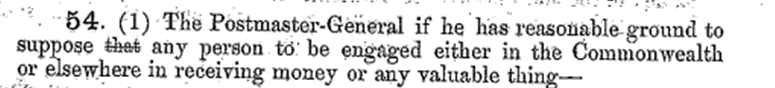

Fortune telling by post was such a problem that it was specifically outlawed by the Post and Telegraph Act of 1901 which gave the postmaster the right to not register or deliver a letter he believed to be “foretelling future events” (Post and Telegraph act 1901).

The Future

Perception of fortune telling has not dramatically altered over time; dismissed by most of the population as a harmless past-time or a con. Fortune telling only became legal in Queensland in 2005 with the repeal of the Vagrants, Gaming and Other Offences Act and is still listed as a crime in the Northern Territory and South Australia when it corresponds with fraud.

Perhaps the greatest difference is the method, now remote fortune telling can be conducted online rather than by post. However, the physical nature of this fortune has ensured that it has survived to make its way into the museum collection, and we don’t think even Beta could have predicted that!

Want to find out more about the contents of the fortune? Stay tuned for the next blog or see the full transcription of the fortune in our online collection.

Sources ↴

“Advertising” Darling Downs Gazette (Qld. : 1881 – 1922) 28 July 1900: 1. Web. 13 Mar 2023

<http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article185587149>.

“Advertising” Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette (Qld. : 1868 – 1919) 25 August 1900: 2. Web. 13 Mar 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article177740084>.

“Advertising” The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) 7 May 1900: 8. Web. 13 Mar 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19031062>.

“Advertising” The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933) 25 May 1901: 15. Web. 13 Mar 2023 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article19127185>.

Amelia Earhart’s palm print and analysis of her character prepared by Nellie Simmons Meier, 28

June. 28 June, 1933. Manuscript/ Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,

<www.loc.gov/item/mcc.038/>

Criminal Code Bill 1899, Queensland Legislative Assembly, Resumption of Committee, 10 October

1899, 325-35 (Qld), <https://digitalcollections.qut.edu.au//id/eprint/4794>

Pietsch, Dr Tamson, host. “Making a Fortune.” The History Lab, season 3, episode 2, Impact Studios,

3 February 2020, <https://historylab.net/s3ep2-making-a-fortune/>

Piper, Alana. “‘A menace and an evil’ Fortune-telling in Australia, 1900–1918,” History Australia 11,

no. 3, (2014): 53-73.

Piper, Alana. “Women’s work: The professionalisation and policing of fortune-telling in

Australia,” Labour History 108 (2015): 1-16.

Post and Telegraph Act 1901 – (Amendment of regulations) – Statutory Rules, 1906 – No. 26

Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1906, <https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2579180637>

Queensland (1938) The Public Acts of Queensland (Reprint) 1828-1936: classified and annotated;

Volume II: Companies to Criminal Law. Butterworth & Co (Australia), Sydney, NSW, <https://digitalcollections.qut.edu.au//id/eprint/3599>

You must be logged in to post a comment.