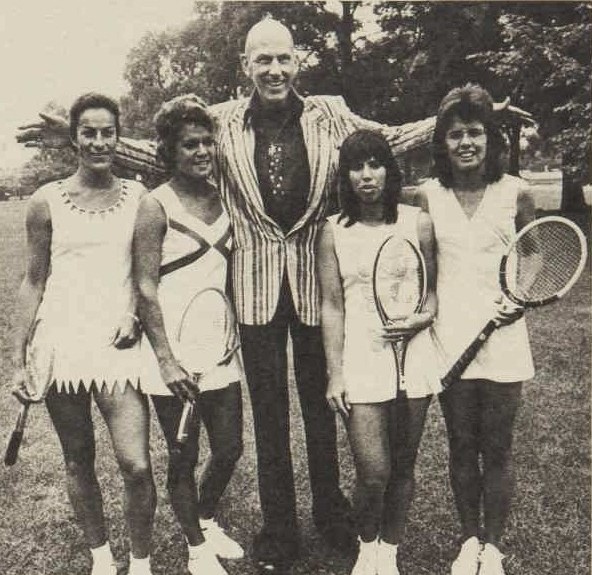

An icon of the tennis fashion world and regarded as the twentieth century’s foremost designer of tennis wear, Cuthbert Collingwood ‘Teddy’ Tinling’s dresses adorned the best-known female players throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, including Billie-Jean King, Martina Navratilova, Chris Evert, Margaret Court and Evonne Goolagong.

In 2023, three of Teddy Tinling’s distinctive creations made their way into Queensland Museum’s collections. Quintessentially Tinling, the custom-made dresses made for former Queensland and Australian tennis champion, Madonna Schacht, are characteristic of the unconventional, playfully provocative models made famous by the designer, yet unique in their custom-made features and in the associated story of the player who wore them.

Born in Gympie, Queensland, on 19 January 1943, Madonna Schacht grew up during the 1950s and 1960s, the ‘golden years’ of Australian tennis, when Australians presided over world tennis, producing players such as Roy Emerson, Rod Laver, Margaret Court, Jan Lehane, Ken Rosewall, Evonne Goolagong, John Newcombe, Judy Dalton, Tony Roche and Mal Anderson.

After her family’s move to Brisbane, Madonna, who had learned and played tennis from a young age, was selected for the Harry Hopman State junior tennis squad which at that time included future Australian, Wimbledon and Grand Slam champions, Rod Laver and Kenneth Fletcher. She won her first national title in 1961 at the age of eighteen, defeating fellow Queensland champion, Robyn Ebbern, 9-7, 6-4.

Selected for the 1962 Australian Women’s Tennis Team to tour England, the United States and Europe, Madonna toured regularly overseas through to the mid-1960s with fellow team members, Lesley Turner, Jan Lehane and Robyn Ebbern– at that time, the cream of Australian women’s tennis. The fifth member of the team, Margaret (Court) Smith, withdrew from the team, citing personal problems with team manager, Nell Hopman. Smith, the top seed for the 1962 women’s final, was defeated in the second round by US champion Billie-Jean Moffitt (King).

Though never reaching the heights achieved by players like Margaret Court, Madonna nevertheless scored many convincing wins over top-ranking players of the time. Most notably, in what the New York Times deemed, ‘the biggest upset of the tournament’, 1 Madonna recorded a resounding 6-3, 8-6 victory over top-seeded Billie Jean Moffitt-King in the quarterfinals of the 1964 Victorian tennis championship. Madonna herself considered her best performance was in winning the Australian Hard Court Singles Title in 1963.2

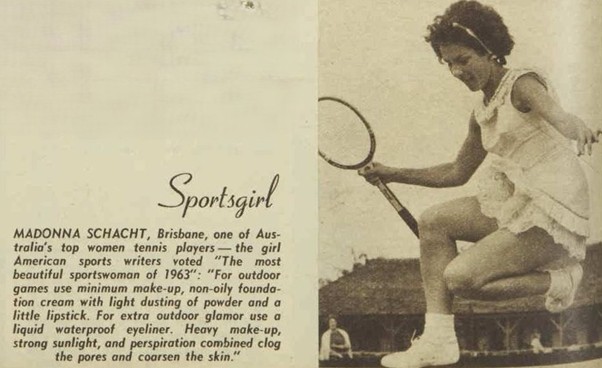

Considered an ‘exceptional beauty’ by the media, Madonna was voted by American sportswriters as ‘the most beautiful sportswoman of 1963’.3 Her image, on and off the tennis court, appeared regularly in local and international news publications and Australian Women’s Weekly, and was featured on the covers of illustrious Sports Illustrated and World Tennis magazines in 1963 and 1965 respectively.

Until 1968 when professional players were admitted to the main tennis circuit, most of the top tennis tournaments were reserved for amateur players. Amateurs received no prize money for competing in these tournaments but were often compensated for travel expenses. As an amateur, Madonna’s travel and some expenses were paid for by the Australian Government, however she and her fellow players were required to pay for their own tennis clothing, shoes and racquets.4 Madonna recalls that though there was little financial reward, the excitement, opportunity to travel and see the world, and the close friendships she formed with her fellow players, compensated for any monetary insufficiency.5

In 2021, Queensland world number one ranked player, Ashleigh Barty won her first Wimbledon women’s singles title in a dress that paid tribute to her hero and role model, Evonne Goolagong. The dress, featuring a scalloped hemline, was based on a dress made by Teddy Tinling, now in the National Museum of Australia, in which Evonne won her own Wimbledon championship in 1971. One of the best-known images of Madonna is that taken by sports photographer, Ed Lacey, in 1966, showing her in action at Wimbledon in an almost identical dress. Madonna said the design was one loved and worn by all top players at that time. As with Evonne Goolagong’s dress, professed to be her favourite,6 Madonna’s dresses reflect her own style and personality, factors always considered by Tinling when designing for women players.

Since tennis first became an acceptable form of exercise and leisure activity for women, each decade has seen notable changes in taste and style. From the 1920s to the 1940s, women began to show more skin, at times causing public outrage, such as when French tennis star, Suzanne Lenglen scandalised Wimbledon in the 1920s when she wore a calf-length skirt, sleeveless and floppy hat by French designer, Jean Patou.7

Shattering the dress codes of the highly segregated and conservative tennis world, with ground-breaking outfits considered ‘naughty’ and ‘racy’,8 such as a controversial pair of lace tennis undershorts worn by Gussie Moran at Wimbledon in 1949, Teddy Tinling is said to have liberated women’s bodies from the restrictive clothing of that time.9 More than a designer, Tinling was also an astute observer of the tennis world. In a career that spanned sixty years, he also wrote several books, recording not just the history but also personal anecdotes and stories from his personal reflections and experience of the game. According to his The New York Times obituary, Tinling is said to have ‘parlayed a pair of lace tennis panties into a tour-de-force fashion career that all but overshadowed his reputation as one of the sport’s most astute observers and historians’.10

From Gussie Moran’s Teddy Tinling designed lacy underpants to Venus Williams’ lingerie-like, black-lace dress with red outlining in 2010, to Serena Williams’ famous Black Panther-inspired black catsuit at the 2018 French Open, women’s tennis fashions have reflected the broader cultural and social changes happening throughout society, often adding grist to the mill of public debate.

Today, Tinling tennis dresses are highly sought-after and collectable, both by individuals and institutions and Madonna Schacht’s Tinling tennis dresses are a significant addition to the Museum’s fashion and sporting collections. A large collection of Tinling tennis wear is currently held in the collections of Australian Sports Museum. There are also numerous examples in other sporting museums such as the Australian Tennis Museum, the International Tennis Hall of Fame and Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum. As mentioned above, Evonne Goolagong’s Tinling dress is now in the collections of the National Museum of Australia, while Billie-Jean King’s famous ‘Battle of the Sexes’ dress is held by the National Museum of American History.

Almost two metres in height, and self-described as a colourful, even ‘flashy’ dresser, Teddy Tinling failed in his decades-long bid to change Wimbledon’s ‘all-whites’ rule and took leave of England in 1975 to head to America where his striking designs were in high-demand. On departing, he vowed to return to Wimbledon each year to see his ‘stars’ and to visit the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum which had opened in 1977, two years after his departure.13 Yet despite his outspoken disdain for ‘pure unrelieved white’, Teddy Tinling’s whimsical white creations speak to women’s personal and collective tennis history, to fashion and to questions of decorum, social distinction, physicality, and femininity.

In Teddy’s own words, ‘I think it is proper I should end up in a museum…but I did want to be immortalised in sequins, not in that dreary white’.14

- ‘Miss Schacht, in an upset, beats Miss Moffitt, 6-3, 8-6’, New York Times, 9 December 1964. ↩︎

- Pers. Comm. Interview, Madonna Schacht, 4 July 2023. ↩︎

- ‘Sportsgirl’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 31 July 1963, p. 56. ↩︎

- Pers. Comm. Interview, Madonna Schacht, 4 July 2023. ↩︎

- Pers. Comm. Interview, Madonna Schacht, 4 July 2023. ↩︎

- Singer, M, ‘The poignant meaning behind Ash Barty’s Wimbledon outfit’, Sydney Morning Herald, 29 June 2021. ↩︎

- Chrisman-Campbell, K, ‘Wimbledon’s first fashion scandal’, The Atlantic, 9 July 2019. ↩︎

- Biography: Ted Tinling, International Tennis Hall of Fame. ↩︎

- Iriart, E, ‘Fashion: Ted Tinling, the pioneer’, Roland-Garros, 2 October 2018. ↩︎

- Thomas, R M Jnr, ‘Ted Tinling, designer, dies at 79; a combiner of tennis and lace’, New York Times, 24 May 1990. ↩︎

- ‘Arrival of Tinling – who made Gussie gorgeous’, Daily Mirror, 5 Nov 1953, p. 57. ↩︎

- Matheson, A 1975, ‘Teddy Tinling goes to America’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 16 July 1975, p. 3. ↩︎

- Matheson, A 1975, ‘Teddy Tinling goes to America’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 16 July 1975, p. 3. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

Leave a comment