Maddy, could you please take us through a typical day for you as the Senior Curator of Maritime Archaeology for Queensland Museum Tropics?

A typical day is a mix of very practical museum work and much bigger-picture thinking. I’ll usually start with emails and project management: coordinating research projects, student supervision through James Cook University, and museum priorities like collections care, exhibitions, or managing shipwreck artefacts.

Some days I’m in the collections, working directly with artefacts from shipwrecks or historic vessels; other days I’m writing grant proposals, research papers, or content that translates complex science into something the public can actually connect with. And then there are days in the field, which might mean diving on a wreck, working with rangers, or environmental scientists.

What I love is that no two days look the same. The role sits right at the intersection of research, public storytelling, and heritage management – protecting sites while also making sure their stories matter to people today.

There are a few subdisciplines in Maritime archaeology, did you ever consider nautical or underwater archaeology before landing on your speciality?

Maritime archaeology is wonderfully broad. You can focus on ships as engineering feats, underwater excavation techniques, coastal landscapes, or living maritime traditions. Early on, I was definitely drawn to underwater archaeology and the technical challenge of working below the surface, but I didn’t always know exactly where I’d land.

Over time, what really captured me was the idea of shipwrecks as more than just sunken objects. They’re cultural time capsules, places where human stories, environmental change, and material culture intersect. That perspective pulled me toward shipwreck archaeology that asks not just how a ship sank, but why it still matters – culturally, environmentally, and socially.

So yes, I explored different pathways, but I think I’ve ended up exactly where my curiosity was always pointing.

Public speaking is a particular passion of yours, you host your own podcast, the Ocean Lounge and have a cult following on social media as the Shipwreck Mermaid. What drives this passion to share your discipline with others and why is this important?

For me, public engagement isn’t an add-on to the job. It’s core to why maritime archaeology matters at all. These sites sit out of sight, underwater, and if people don’t know about them, they’re very easy to forget or damage.

The podcast and social media came from a real frustration early in my career: incredible research was being done, but the stories weren’t reaching the people who actually live near these sites, dive on them, or vote on policies that affect their protection.

I genuinely believe that if people feel connected to a shipwreck (if they understand the human stories, the tragedy, the wonder) they’re far more likely to care about protecting it. Public speaking, the podcast and social media lets me bridge that gap between academia and everyday curiosity, and that’s incredibly powerful.

One of the better-known shipwrecks in Australia is SS Yongala*, known as “Australia’s Titanic”, which sank in 1911 and sits 16 km from Ayr. You have a particular interest in this shipwreck, what is the significance of this site and what has been done to preserve it?

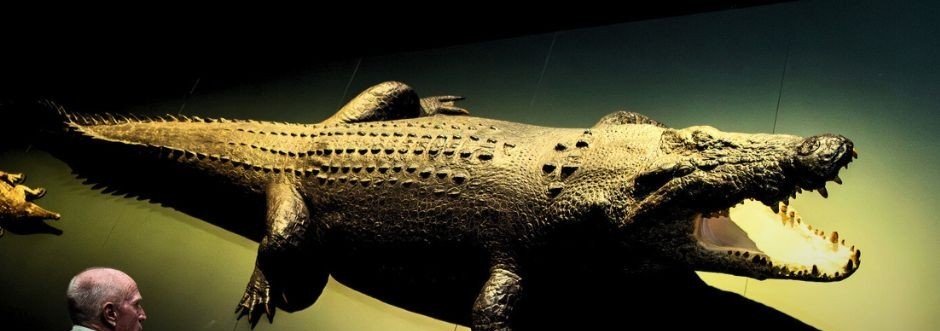

SS Yongala is extraordinary because it’s significant in multiple ways at once. Historically, it’s a tragic loss of life — 122 people lost in 1911 — and it represents a very human moment in Australia’s maritime past.

But what makes Yongala globally remarkable is what has happened since. Over more than a century, it’s become one of the most biodiverse artificial reefs in the world. The shipwreck now supports entire ecosystems (corals, fish, rays, sharks) and it’s a living example of how cultural heritage and natural heritage can become deeply intertwined.

Protection-wise, Yongala is a protected historic shipwreck under Australian law, and access is carefully managed. There’s ongoing research, monitoring, and collaboration between heritage managers, scientists, and the dive industry to balance protection with public access. It’s a great case study for how preservation doesn’t mean locking something away, it means managing it responsibly for us all.

Maddy, we must ask for any avid divers out there, if someone finds a shipwreck, can they go treasure hunting or will that land them in hot water?

Short answer: no — and yes, it can land you in hot water.

In Australia, shipwrecks are protected under heritage legislation, and that protection applies whether the wreck is 100 years old or much younger. Removing artefacts, disturbing the site, or even anchoring incorrectly can cause irreversible damage.

Heritage protection isn’t about stopping discovery or access, it’s about protecting context. Once you remove an object from a wreck, you’ve destroyed information that can never be recovered. If someone thinks they’ve found a shipwreck, the best thing they can do is record the location, take non-invasive photos if it’s safe, and report it to the relevant authority.

As maritime archaeologists, there are so few of us, with such a big job. We love to work with wreck discoverers to investigate new sites. That way, the site can be properly assessed, protected, and its story preserved.

*Yongala means good water in the Ngadjuri language of the Ngadjuri nation of Mid-North South Australia.

Leave a comment