Written by Charlotte Lethbridge, Assistant Collection Manager, Cultures & Histories

In late 2020, the Social History team at Queensland Museum Kurilpa, Brisbane, received a remarkable donation—an exquisite two-piece dress worn by Mary Stuart for her 1881 wedding to Marburg timber merchant and sugar mill proprietor Thomas Lorimer Smith.

A much-loved feature of children’s costume boxes for over a century, the dress had served as a silent witness to a pivotal period in the early European settlement of the Ipswich and Rosewood Scrub region, lands traditionally owned by the Jagera people.

The contributions of women like Mary are often overlooked by the historical record. But by carefully examining the silk threads of Mary’s wedding dress, we can begin to unravel the hidden stories of resilience, strength, and quiet heroism of Queensland women.

Front and back views of Mary Smith’s wedding dress. Images: Queensland Museum. Photographer: Peter Waddington.

A stitch in time: Australian bridal fashion in the 19th century

Before its captivating narrative could be revealed, Mary’s wedding dress was carefully wrapped and placed in a special low-temperature freezer—a crucial step to remove any unwelcome pests. From there, it made its way to the Social History lab, where every pleat, button, and bow was documented in Queensland Museum’s extensive database.

Mary’s dress is typical of the bustle silhouette popular in Australia during the 1870s and 1880s, marking a shift from the cumbersome crinolines of earlier decades. Crinolines were as hazardous as they were impractical, with skirt fires a common and often fatal occurrence.

Although Australian fashion closely mirrored European trends, the white wedding dress, popularised by Queen Victoria after her 1840 marriage to Prince Albert, was slow to catch on in Australia. For pragmatic brides like Mary, practicality took precedence over the allure of a dress that would only be worn once.

Mary’s practicality and resourcefulness are further highlighted by an intriguing discovery. A microscopic analysis of the lace collar revealed that the synthetic fabric used wasn’t commercially available until the 20th century. This indicates that Mary had altered her dress to keep up with evolving fashions.

The fabric of Mary’s dress also tells a story about the period’s textile practices. Silk, often priced by weight, was treated with lead or tin salts to increase its density and cost. While weighted silk produced a rustling sound synonymous with wealth and sophistication, the metallic salts caused the delicate silk threads to shatter over time. Fortunately, Mary’s dress shows only minor signs of wear, a testament to its quality and the skill of its creator.

Beyond the seams: unravelling hidden stories

Born on 3 January 1860 at Fowlis Easter in Perthshire, Scotland, Mary worked as a housekeeper to her widowed uncle in Edinburgh before setting her sights on a new adventure in Australia. Mary’s 46-day voyage aboard the SS Aconcagua brought her to the bustling port of Melbourne on 6 October 1880. From there, she made her way to Marburg where her parents and younger siblings had settled two years prior.

It was in Marburg that Mary met Thomas Lorimer Smith, a man whose entrepreneurial spirit would shape the town’s landscape for years to come. Mary and Thomas were wed on 24 May 1881 at the residence of Mary’s father, James Stuart, a teacher at the newly opened Frederick State School—later renamed Marburg State School. Thomas’ joinery works, sugar mill, and distillery were the principal commercial features of Marburg. An active member of the community, Thomas spearheaded the establishment of the Marburg School of Arts in 1885, installed the first telephone system in Queensland, and negotiated with the Edison Electric Light Company to supply power to several buildings in the town, making Marburg one of the earliest townships in Queensland to use electricity.

South Sea Islander labour played a crucial role in Thomas’ business enterprises. From the early 1860s, tens of thousands of South Sea Islanders were coerced into poorly paid manual labour in the sugar and pastoral industries. Thomas employed time-expired South Sea Islanders who, after completing their initial three-year agreements, remained in Queensland. However, this continued employment did not always translate to contentment, with several of Thomas’ employees appearing in the Marburg Court House on absconding charges.

Woodlands: from prosperity to tragedy

Mary and Thomas lived with their 11 children at Woodlands, an imposing residence designed by esteemed Ipswich architect George Brockwell Gill, whose other works include Ipswich Girls’ Grammar School, Ipswich Technical College, and the now demolished Brynhyfryd Castle at Blackstone.

Boasting eight bedrooms, a lookout tower, and red cedar panelling throughout, Woodlands stood testament to Thomas’ confidence in the future. But the tranquillity and grandeur of Woodlands would soon be disrupted by the tumultuous events of the 1890s. Economic depression and industrial disputes such as the 1894 Australian shearers’ strike intertwined with personal tragedy, leading to devastating consequences for both the Smith and Stuart families.

On 3 August 1894 Mary’s younger brother, William Scott Stuart, drowned at 29 years of age. He had been swimming a horse across a flooded channel at Cambridge Downs following an act of arson that destroyed the shearing shed where he was employed as an engineer. To compound the family’s grief, exactly one month later, Mary’s father succumbed to throat cancer at the age of 64.

Thomas was forced to take out a substantial mortgage on the Woodlands estate in 1897 after unreliable rainfall led to a decline in sugar cultivation. In January 1931, Mary and Thomas moved to Kanimbla, Eagle Junction. Thomas died in February of the same year, leaving Mary in the care of her sister Hannah and son Alan. Mary’s daughter Mary Elizabeth, affectionately known as Polly, stepped into the role of companion after Hannah died in 1938. Stenotypist to the Chief Engineer of Queensland Railways, Polly had never married after her fiancé was killed in World War I.

Woodlands was sold to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brisbane in 1944 and in 1945, the Society of the Divine Word established St Vincent’s Seminary at Woodlands, offering sanctuary to missionaries evacuated from New Guinea. In 1986, Ipswich Grammar School acquired the property and in 2002 it was sold to a local family who opened its doors to the public for the first time in 110 years. Today, Woodlands is a privately owned luxury country retreat, offering guests a glimpse into the estate’s elegant past.

A legacy in blue: Mary’s lasting impact

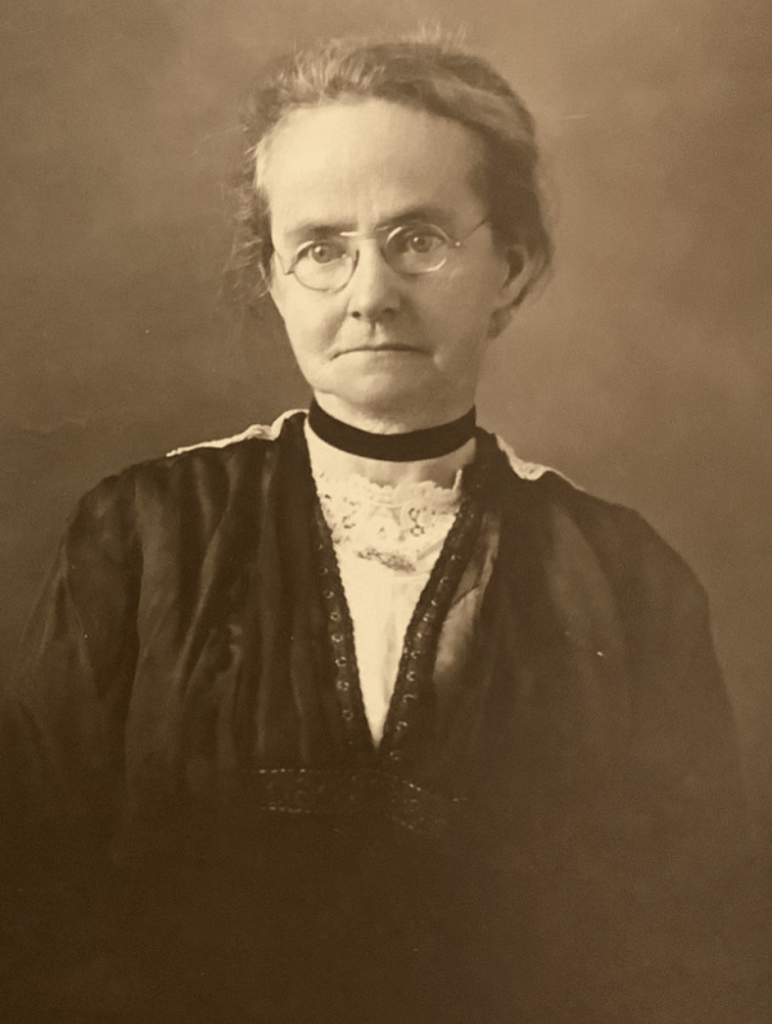

Thomas’ business pursuits may have dominated local headlines, but it was Mary who transformed Woodlands into a haven for visiting relatives, her generosity knowing no bounds. Described by living descendants as a stern presence, Mary maintained order with a shake of her walking stick. But the watchful eye she kept over her grandchildren was softened by moments of warmth and joy. At Kanimbla, Mary created cherished Christmas memories for her grandchildren, complete with special appearances from Santa Claus.

Mary passed away on 5 June 1942 at the age of 82, surviving her husband by 11 years. From her stern demeanour to the Christmas festivities she so lovingly orchestrated, Mary’s steadfast presence triumphed over economic hardship and personal tragedy. Her wedding dress, now under the careful guardianship of Queensland Museum, stands as a reminder of the countless untold stories of Queensland women—a legacy in blue, delicately woven into the fabric of Queensland’s history.

Mary Smith’s wedding dress can be viewed online as part of Queensland Museum’s Online Collections.

You must be logged in to post a comment.