A student of Western Classical music reflects on A traditional instrument in the Marson Collection, Queensland Museum

Written by Kristina Newton

With many thanks to Isaac Te Awa, Safua Akeli Amaama, and staff at Te Papa Tongarewa (Museum of New Zealand), and to Hinewehi Mohi, for cultural advice and guidance on this piece. Thank you also to Rob Thorne for allowing us to include your videos, and to Hinewehi Mohi and Lane Worrall for permission to include the artwork featuring Raukatauri.

For me, my musical instrument (the clarinet) represents a connection to a longstanding musical tradition, to an intimate community comprising a broad range of instruments (the orchestra), and to an art form (Western classical music) that I’ve dedicated much of my life to. But different instruments from different cultures mean different things to the people who have identified with them, through time.

For Charles Marson, the 800-plus musical instruments he gathered from cultures throughout the world represented a passion for music and anthropology. One instrument from his collection—now known as the Marson Collection, housed at Queensland Museum—is a pūtōrino, an instrument of the Māori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Marson acquired this pūtōrino from a dealer of Indigenous Pacific art in 1991. However, several similar instruments that exist in international collections were originally transported overseas by American merchants. Around the start of the 19th century, commercial voyages sailed throughout the Pacific trading tobacco and clothing, along with then-exotic commodities such as coffee and sugar, and occasionally cultural treasures such as this instrument (Mackintosh, 2012).

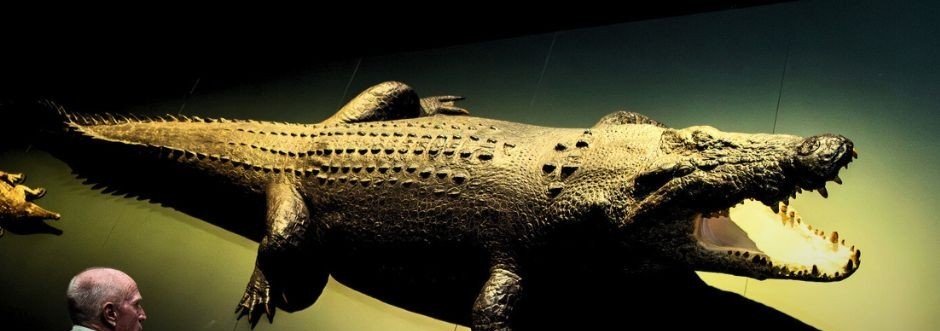

The pūtōrino is unique to Māori culture, and no instruments of the same design and function have been identified anywhere else in the world. It is an especially significant instrument culturally, as it symbolises Raukatauri, the goddess of flute music (see Figure). Legend has it that Raukatauri loved her flute so much that she transformed into a moth (pēpepe) and made a cocoon out of her flute, creating a home for herself inside. A male moth heard her entrancing voice and they fell in love with each other. Together they hatched baby caterpillars which nibbled a hole in the cocoon and left to spread their music throughout the world.

Caption and photo from Te Ara. Model: Hinewehi Mohi; Body Paint Artist: Myrtha Heydenrijk; Graphic Designer: Lane Worrall; Photographer: Chris Traill. Used with permission.

The late Dr Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns were both masters of traditional instruments, and worked tirelessly, individually and together, to revive taonga puoro. (Dr Melbourne mentored the well-known Māori musician Dame Hinewehi Mohi, featured in the previous image.) In the following video, Melbourne and Nunns join Aroha Yates-Smith to they discuss and perform music from their album “Te Hekenga-a-rangi”.

The next video, made in 2012, is of Richard Nunns playing the pūtōrino.

The pūtōrino is very versatile. It can be played at the small hole at the top of the instrument either trumpet-style, creating a male voice, or cross-blown like a flute, creating the female voice of Raukatauri (Flintoff, 2014). It can also be blown at the larger hole located mid-way down the instrument. A range of around two octaves can be achieved by manipulating the size of the hole midway down the instrument with fingers; this produces a spectrum of tone qualities, from wistful to penetrating, as shown in the following video of Rob Thorne.

For Māori people, the pūtōrino is an expression of their culture on many levels. Beyond symbolising traditional mythology, the visual artistry of the instrument—and of course its musical uses—are central to its importance. The Māori term for traditional musical instruments, taonga puoro, translates to ‘singing treasures.’ The concept encapsulates many facets of a musical instrument that aren’t usually perceived to be part of the music-making process in Western culture.

For example, the finding of materials and carving of instruments is considered by Māori people to be a spiritual process. This connection with the physicality of musical instruments makes for an intimate relationship between musician and instrument, and allows for the idea that the instrument itself can grow, rather than being a static object. For Māori people, the pūtōrino and other traditional instruments are far more than objects. Rather, according to Isaac Te Awa, curator Mātauranga Māori at Te Papa Tongarewa (Museum of New Zealand), they require “a meaningful connection and awareness of objects in the environment, and a deep sense of knowing oneself”.

As an undergraduate music student, I have learnt that we gain a superpower from learning about instruments from other cultures: namely, a widened perspective on our relationships with our own instruments. If you are a musician, do you see yourself as an equal to the instruments that you play? What is the relationship between you, your instrument, and the greater environment in which your sound is heard?

And if you do not think of yourself as a musician, what makes you think of yourself in that way? Humming along to an advertisement jingle, ringing a doorbell, perhaps even listening to the rhythm of your footsteps when you wear your favourite shoes: we can all express ourselves creatively through sound, if only we become aware of our auditory signatures.

“In Māori traditional thinking, one belongs to one’s creative work as much as the creative work belongs to its creator,” says Aotearoa / New Zealand composer Robert Wiremu (2020, p. 44). How might this perspective influence our relationship to music or to other creative work in our lives?

For me, as a music student and a newcomer to Māori traditions, learning about pūtōrino is helping me forge a new relationship of open-mindedness, expression, and connection with my instrument. I hope my newcomer reflections on pūtōrino and its cultural meanings also strike a creative chord with you too.

Note. This piece was written in January 2024 by Kristina Newton, Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University, in the context of a Griffith Honours College Summer Bursary Project, under the guidance of Dr Catherine Grant (QCGU) and Karen Kindt (Queensland Museum).

References and Further Reading

Flintoff, B. (2014, October 22). Māori musical instruments – taonga puoro. The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-musical-instruments-taonga-puoro/print

Haumanu Collective. (2021a). Taonga Puoro Haumanu Collective. Haumanu Collective. https://www.haumanucollective.com/taonga-puoro/

Haumanu Collective. (2021b, October 11). Pūtōrino. Haumanu Collective. https://www.haumanucollective.com/putorino/

Hill, Keith (2011, January 23). “Te Hekenga-a-rangi” (Excerpt 1) – Hirini Melbourne and Richard Nunns. [YouTube clip.] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FaH6s-twdzU

Mackintosh, L. (2012). Holding on to Objects in Motion: Two Māori Musical Instruments in the Peabody Essex Museum. Material Culture Review, 74–75, 86–101.

Museum of New Zealand. (2012, December 12). Richard Nunns playing the pūtōrino [YouTube clip]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3xeHyxErPV8

Reweti, L. (2024, January 12). Museum Notebook: The song of Hine Raukatauri and the utterly unique pūtōrino. NZ Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/whanganui-chronicle/news/museum-notebook-the-song-of-hine-raukatauri-and-the-utterly-unique-putorino/EU7ZDRD6M5C44SGGUCU2PM7VMU/

Te Awa, I. (2021, November 21). Te Pū me te Oro: The Crafting of Taonga Pūoro. Pantograph Punch. https://www.pantograph-punch.com/posts/te-pu-me-te-oro

Te Papa Tongarewa. (2016, June 10). Māori musical instruments. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, NZ. https://www.tepapa.govt.nz/discover-collections/read-watch-play/maori/maori-musical-instruments

Thorne, Rob. (2014, April 9). Rob Thorne plays Pūtōrino on Tiritiri Matangi Island. [YouTube clip.] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIOzr_s59KA

Thorne, Rob. (2022, April 15). Te Manawa o Raukatauri – Live (Pūtōrino by Rob Thorne, Ngāti Tumutumu). [YouTube clip.] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFaZQe8ElAU

Traill, C., & Taonga, N. Z. M. for C. and H. T. M. (2013, September 5). Raukatauri [Web page]. Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. https://teara.govt.nz/en/photograph/40186/raukatauri

Wiremu, R. (2020). Language Preservation and Māori: A Musical Perspective. The Choral Journal, 60(8), 41–46.

You must be logged in to post a comment.